Dracula

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the novel. For the eponymous character, see Count Dracula. For other uses, see Dracula (disambiguation).

The cover of the first edition

|

|

| Author | Bram Stoker |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Horror, Gothic |

| Publisher | Archibald Constable and Company (UK) |

|

Publication date

|

26 May 1897 |

| OCLC | 1447002 |

Famous for introducing the character of the vampire Count Dracula, the novel tells the story of Dracula's attempt to move from Transylvania to England so he may find new blood and spread the undead curse, and the battle between Dracula and a small group of men and women led by Professor Abraham Van Helsing.

Dracula has been assigned to many literary genres including vampire literature, horror fiction, the gothic novel and invasion literature. The novel touches on themes such as the role of women in Victorian culture, sexual conventions, immigration, colonialism, and post-colonialism. Although Stoker did not invent the vampire, he defined its modern form, and the novel has spawned numerous theatrical, film and television interpretations.

Contents

Plot summary

Stoker's handwritten notes on the personnel of the novel

The tale begins with Jonathan Harker, a newly qualified English solicitor, visiting Count Dracula in the Carpathian Mountains on the border of Transylvania, Bukovina, and Moldavia, to provide legal support for a real estate transaction overseen by Harker's employer. At first enticed by Dracula's gracious manners, Harker soon realizes that he is Dracula's prisoner. Wandering the Count's castle against Dracula's admonition, Harker encounters three female vampires, called "the sisters", from whom he is rescued by Dracula. After the preparations are made, Dracula leaves Transylvania and abandons Harker to the sisters. Harker barely escapes from the castle with his life.

Not long afterward, a Russian ship, the Demeter, having weighed anchor at Varna, runs aground on the shores of Whitby. The captain's log narrates the gradual disappearance of the entire crew, until the captain alone remained, himself bound to the helm to maintain course. An animal resembling "a large dog" is seen leaping ashore. The ship's cargo is described as silver sand and boxes of "mould", or earth, from Transylvania.

Soon Dracula is tracking Harker's fiancée, Wilhelmina "Mina" Murray, and her friend, Lucy Westenra. Lucy receives three marriage proposals from Dr. John Seward, Quincey Morris, and the Hon. Arthur Holmwood (later Lord Godalming). Lucy accepts Holmwood's proposal while turning down Seward and Morris, but all remain friends. Dracula communicates with Seward's patient Renfield, an insane man who wishes to consume insects, spiders, birds, and rats to absorb their "life force", and therefore assimilate to Dracula himself. Renfield is able to detect Dracula's presence and supplies clues accordingly.

When Lucy begins to waste away suspiciously, Seward invites his old teacher, Abraham Van Helsing, who immediately determines the cause of Lucy's condition but refuses to disclose it. While both doctors are absent, Lucy and her mother are attacked by a wolf; Mrs. Westenra, who has a heart condition, dies of fright, and Lucy dies soon after. Following Lucy's death, the newspapers report children being stalked in the night by, in their words, a "bloofer lady" (i.e., "beautiful lady").[2] Van Helsing, knowing Lucy has become a vampire, confides in Seward, Lord Godalming, and Morris. The suitors and Van Helsing track her down and, after a confrontation with her, stake her heart, behead her, and fill her mouth with garlic. Around the same time, Jonathan Harker arrives from Budapest, where Mina marries him after his escape, and he and Mina join the coalition against Dracula.

After Dracula learns of Van Helsing's plot against him, he attacks Mina on three occasions, and feeds Mina his own blood to control her. Under his influence, Mina oscillates from consciousness to a semi-trance during which she perceives Dracula's surroundings and actions. After the protagonists sterilize all of his lairs in London by putting pieces of consecrated host in each box of Transylvanian earth, Dracula flees to Transylvania, pursued by Van Helsing and the others under the guidance of Mina. In Transylvania, Van Helsing repulses and later destroys the vampire "sisters". Upon discovering Dracula being transported by Gypsies, Harker shears Dracula through the throat with a kukri while the mortally wounded Quincey stabs the Count in the heart with a Bowie knife. Dracula crumbles to dust, and Mina is restored to health.

The book closes with a note on Mina's and Jonathan's married life and the birth of their son, whom they name after all four members of the party, but address as "Quincey".

Deleted ending

The original final chapter was removed, in which Dracula's castle falls apart as he dies, hiding the fact that vampires were ever there.[3]Characters

- Jonathan Harker: A solicitor sent to do business with Count Dracula; Mina's fiancé and prisoner in Dracula's castle.

- Count Dracula: A Transylvanian noble who has purchased a house in London.

- Wilhelmina "Mina" Harker (née Murray): A schoolteacher and Jonathan Harker's fiancée.

- Lucy Westenra: A 19-year-old aristocrat; Mina's best friend; Arthur's fiancée and Dracula's first victim.

- Arthur Holmwood: Lucy's suitor and later fiancé.

- John Seward: A doctor; one of Lucy's suitors and a former student of Van Helsing.

- Abraham Van Helsing: A Dutch doctor and professor; John Seward's teacher; and, a vampire hunter.

- Quincey Morris: An American cowboy and explorer; and one of Lucy's suitors.

- Renfield: A lawyer whom Dracula turned mad.

- "Weird Sisters": Three siren-like vampire women who serve Dracula. In some of the plays, films etc. that came after the novel they are referred to as the Brides of Dracula.

Background

Between 1879 and 1898, Stoker was a business manager for the world-famous Lyceum Theatre in London, where he supplemented his income by writing a large number of sensational novels, his most famous being the vampire tale Dracula published on 26 May 1897.[4]:269 Parts of it are set around the town of Whitby, where he spent summer holidays. Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, authors such as H. Rider Haggard, Rudyard Kipling, Robert Louis Stevenson, Arthur Conan Doyle, and H. G. Wells wrote many tales in which fantastic creatures threatened the British Empire. Invasion literature was at a peak, and Stoker's formula of an invasion of England by continental European influences was by 1897 very familiar to readers of fantastic adventure stories. Victorian readers enjoyed it as a good adventure story like many others, but it would not reach its iconic legendary status until later in the 20th century when film versions began to appear.[5]

Shakespearean actor and friend of Stoker's, Sir Henry Irving

was a possible real-life inspiration for the character of Dracula. The

role was tailor-made to his dramatic presence, gentlemanly mannerisms

and affinity for playing villain roles. Irving, however, never agreed to

play the part on stage.

Despite being the most widely known vampire novel, Dracula was not the first. It was preceded and partly inspired by Sheridan Le Fanu's 1871 "Carmilla", about a lesbian vampire who preys on a lonely young woman, and by Varney the Vampire, a lengthy penny dreadful serial from the mid-Victorian period by James Malcolm Rymer. The image of a vampire portrayed as an aristocratic man, like the character of Dracula, was created by John Polidori in "The Vampyre" (1819), during the summer spent with Frankenstein creator Mary Shelley, her husband, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron in 1816. The Lyceum Theatre, where Stoker worked between 1878 and 1898, was headed by the actor-manager Henry Irving, who was Stoker's real-life inspiration for Dracula's mannerisms and who Stoker hoped would play Dracula in a stage version.[6] Although Irving never did agree to do a stage version, Dracula's dramatic sweeping gestures and gentlemanly mannerisms drew their living embodiment from Irving.[6]

The Dead Un-Dead was one of Stoker's original titles for Dracula, and up until a few weeks before publication, the manuscript was titled simply The Un-Dead. Stoker's notes for Dracula show that the name of the count was originally "Count Wampyr", but while doing research, Stoker became intrigued by the name "Dracula", after reading William Wilkinson's book Account of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia with Political Observations Relative to Them (London 1820),[7] which he found in the Whitby Library, and consulted a number of times during visits to Whitby in the 1890s.[8] The name Dracula was the patronym (Drăculea) of the descendants of Vlad II of Wallachia, who took the name "Dracul" after being invested in the Order of the Dragon in 1431. In the Romanian language, the word dracul (Romanian drac "dragon" + -ul "the") can mean either "the dragon" or, especially in the present day, "the devil".[9]

The novel has been in the public domain in the United States since its original publication because Stoker failed to follow proper copyright procedure. In the United Kingdom and other countries following the Berne Convention on copyrights, however, the novel was under copyright until April 1962, fifty years after Stoker's death.[10] When F. W. Murnau's unauthorized film adaptation Nosferatu was released in 1922, the popularity of the novel increased considerably, owing to the controversy caused when Stoker's widow tried to have the film removed from public circulation.[11]

Reaction and scholarly criticism

1899 first American edition, Doubleday & McClure, New York.

According to literary historians Nina Auerbach and David J. Skal in the Norton Critical Edition, the novel has become more significant for modern readers than it was for contemporary Victorian readers, most of whom enjoyed it just as a good adventure story; it only reached its broad iconic legendary classic status later in the 20th century when the movie versions appeared.[13] It did not make much money for Stoker; the last year of his life he was so poor that he had to petition for a compassionate grant from the Royal Literary Fund,[14] and in 1913 his widow was forced to sell his notes and outlines of the novel at a Sotheby's auction, where they were purchased for a little over 2 pounds.[15] But when F. W. Murnau's unauthorized adaptation of the story in the form of Nosferatu was released in theatres in 1922, Stoker's widow took affront, and during the legal battle that followed, the novel's popularity started to grow. Nosferatu was followed by a highly successful stage adaptation, touring the UK for three years before arriving in the US where Stoker's creation caught Hollywood's attention, and after the American 1931 movie version was released, the book has never been out of print.[16] However, some Victorian fans were ahead of the time, describing it as "the sensation of the season" and "the most blood-curdling novel of the paralysed century".[17] Sherlock Holmes author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote to Stoker in a letter, "I write to tell you how very much I have enjoyed reading Dracula. I think it is the very best story of diablerie which I have read for many years."[18] The Daily Mail review of 1 June 1897 proclaimed it a classic of Gothic horror, "In seeking a parallel to this weird, powerful, and horrorful story our mind reverts to such tales as The Mysteries of Udolpho, Frankenstein, The Fall of the House of Usher ... but Dracula is even more appalling in its gloomy fascination than any one of these."[19]

Similarly good reviews appeared when the book was published in the U.S. in 1899. The first American edition was published by Doubleday & McClure in New York.

In the last several decades, literary and cultural scholars have offered diverse analyses of Stoker's novel and the character of Count Dracula. C.F. Bentley reads Dracula as an embodiment of the Freudian id.[20] Carol A. Senf reads the novel as a response to the powerful New Woman,[21] while Christopher Craft sees Dracula as embodying latent homosexuality.[22] Stephen D. Arata interprets the events of the novel as anxiety over colonialism and racial mixing,[23] and Talia Schaffer construes the novel as an indictment of Oscar Wilde.[24] Franco Moretti reads Dracula as a figure of monopoly capitalism,[25] though Hollis Robbins suggests that Dracula's inability to participate in social conventions and to forge business partnerships undermines his power.[26][27] Richard Noll reads Dracula within the context of 19th century alienism (psychiatry) and asylum medicine.[28] D. Bruno Starrs understands the novel to be a pro-Catholic pamphlet promoting proselytization.[29]

Historical and geographical references

Although Dracula is a work of fiction, it does contain some historical references. The historical connections with the novel and how much Stoker knew about the history are a matter of conjecture and debate.Following the publication of In Search of Dracula by Radu Florescu and Raymond McNally in 1972, the supposed connections between the historical Transylvanian-born Vlad III Dracula of Wallachia and Bram Stoker's fictional Dracula attracted popular attention. During his main reign (1456–1462), "Vlad the Impaler" is said to have killed from 40,000 to 100,000 European civilians (political rivals, criminals, and anyone he considered "useless to humanity"), mainly by impaling. The sources depicting these events are records by Saxon settlers in neighbouring Transylvania, who had frequent clashes with Vlad III. Vlad III is revered as a folk hero by Romanians for driving off the invading Ottoman Turks, of which his impaled victims are said to have included as many as 100,000.[30]

Vlad the Impaler; also known as Vlad Dracula.

Stoker came across the name Dracula in his reading on Romanian history, and chose this to replace the name (Count Wampyr) originally intended for his villain. Some Dracula scholars, led by Elizabeth Miller, argue that Stoker knew little of the historic Vlad III except for the name "Dracula", whereas in the novel, Stoker mentions the Dracula who fought against the Turks, and was later betrayed by his brother, historical facts which unequivocally point to Vlad III:

Who was it but one of my own race who as Voivode crossed the Danube and beat the Turk on his own ground? This was a Dracula indeed! Woe was it that his own unworthy brother, when he had fallen, sold his people to the Turk and brought the shame of slavery on them! Was it not this Dracula, indeed, who inspired that other of his race who in a later age again and again brought his forces over the great river into Turkey-land; who, when he was beaten back, came again, and again, though he had to come alone from the bloody field where his troops were being slaughtered, since he knew that he alone could ultimately triumph! (Chapter 3, pp 19)The Count's identity is later speculated on by Professor Van Helsing:

He must, indeed, have been that Voivode Dracula who won his name against the Turk, over the great river on the very frontier of Turkey-land. (Chapter 18, p 145)Many of Stoker's biographers and literary critics have found strong similarities to the earlier Irish writer Sheridan Le Fanu's classic of the vampire genre, Carmilla. In writing Dracula, Stoker may also have drawn on stories about the sídhe,[citation needed] some of which feature blood-drinking women. The folkloric figure of Abhartach has also been suggested as a source.[31]

In 1983, McNally additionally suggested that Stoker was influenced by the history of Hungarian Countess Elizabeth Bathory, who tortured and killed between 36 and 700 young women.[32] It was later commonly believed that she committed these crimes to bathe in their blood, believing that this preserved her youth.[33]

In her book The Essential Dracula, Clare Haword-Maden opined the castle of Count Dracula was inspired by Slains Castle, at which Bram Stoker was a guest of the 19th Earl of Erroll.[34] According to Miller, he first visited Cruden Bay in 1893, three years after work on Dracula had begun. Haining and Tremaine maintain that during this visit, Stoker was especially impressed by Slains Castle's interior and the surrounding landscape. Miller and Leatherdale question the stringency of this connection.[35] Possibly, Stoker was not inspired by a real edifice at all, but by Jules Verne's novel The Carpathian Castle (1892) or Anne Radcliffe's The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794).[36] A third possibility is that he copied information about a castle at Vécs from one of his sources on Transylvania, the book by Major E.C. Johnson.[37] A further option is that Stoker saw an illustration of Castle Bran (Törzburg) in the book on Transylvania by Charles Boner, or read about it in the books by Mazuchelli or Crosse.[38] Many of the scenes in Whitby and London are based on real places that Stoker frequently visited, although in some cases he distorts the geography for the sake of the story. One scholar has suggested that Stoker chose Whitby as the site of Dracula's first appearance in England because of the Synod of Whitby, given the novel's preoccupation with timekeeping and calendar disputes.[26]

Daniel Farson, Leonard Wolf, and Peter Haining have suggested that Stoker received much historical information from Ármin Vámbéry, a Hungarian professor he met at least twice. Miller argues "there is nothing to indicate that the conversation included Vlad, vampires, or even Transylvania" and that, "furthermore, there is no record of any other correspondence between Stoker and Vámbéry, nor is Vámbéry mentioned in Stoker's notes for Dracula."[39]

Adaptations

For more details on this topic, see Dracula in popular culture.

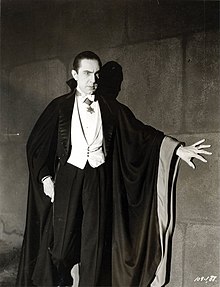

Bela Lugosi as Dracula (1931)

The character of Count Dracula has remained popular over the years, and many films have used the character as a villain, while others have named him in their titles, including Dracula's Daughter and The Brides of Dracula. As of 2009, an estimated 217 films feature Dracula in a major role,[40] a number second only to Sherlock Holmes (223 films).[41]

Most adaptations do not include all the major characters from the novel. The Count is always present, and Jonathan and Mina Harker, Dr. Seward, Dr. Van Helsing, and Renfield usually appear as well. The characters of Mina and Lucy are often combined into a single female role. Jonathan Harker and Renfield are also sometimes reversed or combined. Quincey Morris and Arthur Holmwood are usually omitted entirely (Bram Stoker's Dracula being a notable exception).

"Dracula's Guest"

In 1914, two years after Stoker's death, the short story "Dracula's Guest" was posthumously published. It was, according to most contemporary critics, the deleted first (or second) chapter from the original manuscript[42] and the one which gave the volume its name,[4]:325 but which the original publishers deemed unnecessary to the overall story."Dracula's Guest" follows an unnamed Englishman traveller as he wanders around Munich before leaving for Transylvania. It is Walpurgis Night, and in spite of the coachman's warnings, the young Englishman foolishly leaves his hotel and wanders through a dense forest alone. Along the way he feels he is being watched by a tall and thin stranger (possibly Count Dracula).

The short story climaxes in an old graveyard, where in a marble tomb (with a large iron stake driven into it), the Englishman encounters a sleeping female vampire called Countess Dolingen. This malevolent and beautiful vampire awakens from her marble bier to conjure a snowstorm before being struck by lightning and returning to her eternal prison. However, the Englishman's troubles are not quite over, as he is dragged away by an unseen force and rendered unconscious. He awakes to find a "gigantic" wolf lying on his chest and licking at his throat; however, the wolf merely keeps him warm and protects him until help arrives.

When the Englishman is finally taken back to his hotel, a telegram awaits him from his expectant host Dracula, with a warning about "dangers from snow and wolves and night".

See also

Notes and references

- James Craig Holte. Dracula Film Adaptations. p. 27. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

Bibliography

- Dalby, Richard and Hughes, William. Bram Stoker: A Bibliography (Westcliff-on-Sea: Desert Island Books, 2005)

- Frayling, Christopher. Vampyres: Lord Byron to Count Dracula (1992) ISBN 0-571-16792-6

- Eighteen-Bisang, Robert and Miller, Elizabeth. Bram Stoker's Notes for Dracula: A Facsimile Edition Toronto: McFarland, 2008, ISBN 978-0-7864-3410-7

- Hughes, William. Beyond Dracula: Bram Stoker's Fiction and its Cultural Contexts (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2000)

- McNally, Raymond T. & Florescu, Radu. In Search of Dracula. Houghton Mifflin Company, 1994. ISBN 0-395-65783-0

- Miller, Elizabeth. Dracula: Sense & Nonsense. 2nd ed. Desert Island Books, 2006. ISBN 1-905328-15-X

- Schaffer, Talia. A Wilde Desire Took Me: the Homoerotic History of Dracula, in: ELH - Volume 61, Number 2 (1994), pp. 381–425.

- Senf, Carol. Science and Social Science in Bram Stoker's Fiction (Greenwood, 2002).

- Senf, Carol. Dracula: Between Tradition and Modernism (Twayne, 1998).

- Spencer, Kathleen. Purity and Danger: Dracula, the Urban Gothic, and the Late Victorian Degeneracy Crisis, in: ELH - Volume 59, Number 1 (1992), pp. 197–225.

- Wolf, Leonard. The Essential Dracula. ibooks, inc., 2004. ISBN 0-7434-9803-8

- Klinger, Leslie S. The New Annotated Dracula. W.W. Norton & Co., 2008. ISBN 0-393-06450-6

- Waters, Colin Gothic Whitby . History Press, 2009 - ISBN 0-7524-5291-6

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Dracula at Project Gutenberg, text version of 1897 edition. PDF

- Dracula from the CELT Project, HTML version of 1897 edition. TEI/XML

- Dracula, New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1897. Scanned first edition from Internet Archive.

Dracula public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Dracula public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Bram Stoker, Dracula and Whitby BBC article

- The Myth of Transylvania, Romanian Website dealing with the Dracula myth and the Western perception of Romania.